By Julia Barnes, Marketing and Communications Assistant

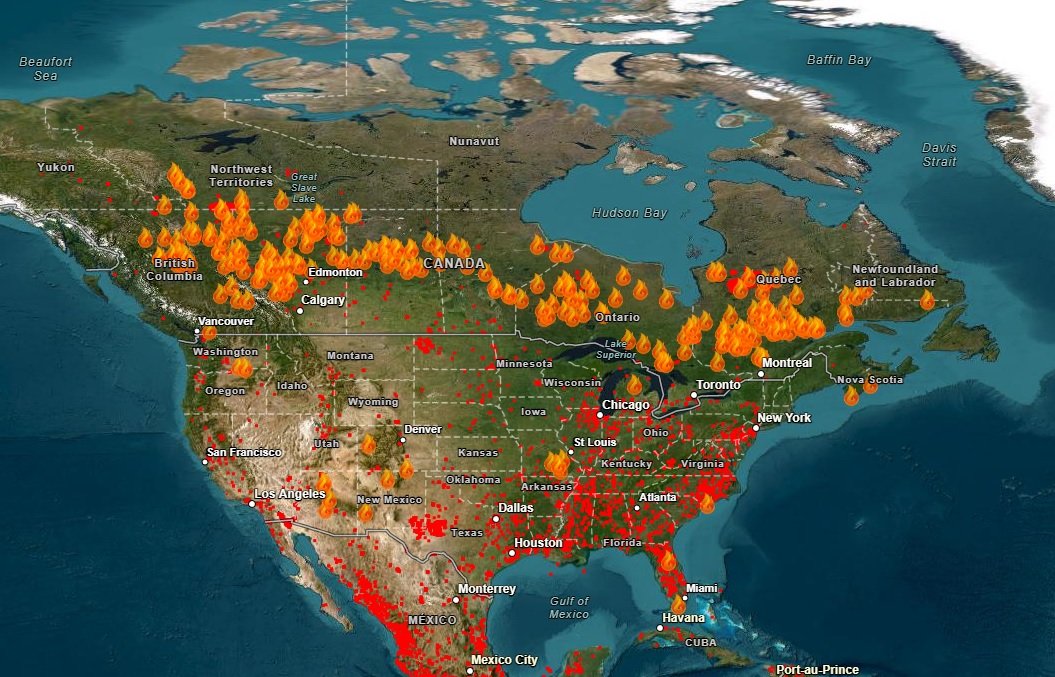

Current state of fires across North America. Image courtesy Fire Information for Resource Management System US/Canada

Forest fires are making daily headlines in Canada right now. The impact of these fires have been felt across the continent, mainly in air quality. However, these fires are interconnected to many other environmental issues like logging, deforestation and embodied carbon.

In this two-part series on Canadian forest fires we chat with some experts who look to shine some light on the complex issue.

Although fires are a natural process in most forests, they are increasing in frequency, severity and extent. We know that climate change is intensifying fires, but what about the impacts from logging?

Extraction has changed the landscape dramatically, creating homogenised plantations that no longer function the same as intact ecosystems.

A recently burned forest with new forest floor growth. Image courtesy Michelle Connolly

Michelle Connolly, ecologist and director of Conservation North, says there’s a big difference between natural, primary forests and those that are industrially managed.

“When you walk into a primary forest, you see a lot of complexity. The forest floor has shrubs, herbs, mosses, and dead logs. There are standing dead trees, fallen dead trees, standing living trees. You get these multi-layered, multi-storied forests.”

“In industrially managed forests, everything is simplified. Here in BC, these fake forests look very uniform, with trees of similar ages, often the same species. You don't see a lot of wildlife.”

Connolly is not sure how much primary forest remains in BC, but estimates it could be as low as 30%. The rest has been degraded by industrial logging, roads and other modern human impacts.

“Older forests are less likely to ignite, and industrial forestry targets those. Research suggests that plantations are less resilient to fire, probably because they are often windier and drier.”

Not only is logging increasing forests’ susceptibility to fire, industrial logging is also a contributor to climate change, says Connolly. “The emissions from logging natural forests are significant because you're disturbing the soil, you're taking out nature's carbon capture and storage system – forests – and you're replacing it with something that's not going to regain that carbon for decades. Storage is the metric that matters when you’re talking about carbon in forests.”

Heavy machinery carrying out salvage logging procedures. Image courtesy Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology

As fires continue to burn across many Canadian provinces, logging companies are already planning to extract damaged trees. Salvage logging is a common practice in Canada that involves removing trees shortly after a natural disturbance such as wildfire. The purpose is to consume the trees before they have a chance to decay.

“When you're in the world of timber, you are looking to remove the burned trees to sell them. If your priority is money you want to get the burned trees out as soon as possible,” Connolly explains. “From an ecological standpoint, that's disastrous.”

Salvage logging inhibits natural regeneration, damages the soil, changes the composition of plant species, and harms wildlife.

Research has shown that logging after a forest fire reduces the presence of small mammals such as hares, squirrels, mice and voles. These animals require standing trees as habitat, but salvage logging removes nearly all standing trees. Without small mammals, the food source for larger predators such as owls, lynx, marten, fisher and coyotes is diminished.

Forests that are allowed to regenerate naturally after a fire have greater diversity and abundance of wildlife.

“Industrial forestry has a mindset that when something dies, you need to get rid of it right away,” says Connolly. “Wildlife biologists argue that the beginning of a tree's value for wildlife is actually after it dies. Think about all the organisms that need dead trees for habitat - small mammals, bats, birds, and insects - all of those organisms rely on death as a process in natural forests.”

While emissions from wildfires have been making news, it’s important to remember that logging releases up to 10 times as much carbon as natural disturbances. Even forests that have been heavily burned still maintain most of their carbon in soil, snags, and down wood.

“There are many reasons for not converting primary forests into industrialised plantations. Potentially increasing the risk of fire is one of those reasons,” says Michelle Connolly.

The government of BC is in the process of developing a framework for biodiversity and ecosystem health. Conservation North believes that the easiest way to do that is to set aside all natural forests as areas of adaptation and mitigation for climate change.

Michelle Connolly of Conservation North went on to say, “We need to leave natural forests alone because they're doing a great job of providing for biodiversity, storing carbon, and providing the amazing sources of clean water, clean air, and oxygen that we all need.”

Keep an eye out for part two of this blog that comes out next week.

Image courtesy of joint study between NRDC, Environmental Defence and Nature Canada